Erotic Art and the Femme Fatale

Would you like to sin

With Elinor Glyn

On a tiger-skin?

Or would you prefer

To err

With her

On some other fur?

During the period known as the Belle Époque, themes such as the beautiful animal-woman, the sphinx, the vampire, the femme fatale, the seductive serpent and Salomé were cultivated and stylized through Symbolic art, at the time considered to be outrageous. Aubrey Beardsley found Japanese shunga (spring pictures) – a collection of erotic woodcuts – an enlightening contrast to prudish, Victorian England. His walls were adorned with prints of Japanese courtesans and their lovers, engaged in complicated acrobatics. Gabriele D’Annunzio was another master of literary eroticism. His cult of Eros and beauty encapsulated the decadent tastes of the time. The ambivalent female of his poetry fulfilled the Symbolist ideal of femme fatales like Salomé.

Edwardian England prized maturity and savoir-faire in a woman. None so captured the tone of the age than the novelist Elinor Glyn and her sister, the couturière, Lucile. Elinor’s Three Weeks, written in 1907, may seem quaint to the modern reader, but with sexuality on almost every page, it became the cause célèbre of its day, the Edwardian equivalent of 50 Shades of Grey. The book was an overnight sensation. Anita Leslie, writing in Edwardians in Love commented, “it did not merely appeal to the romantic aspirations of kitchenmaids, but to the kitchenmaid in the heart of every great lady in Europe.”

Meanwhile, Glyn’s couture gown making sister’s clients included some of the great courtesans or ‘grandes horizontales’ of the day, such as La Belle Otero and Mata Hari. In the closing years of the Belle Époque, strong, independent women, including Sarah Bernhardt and Isadora Duncan, were among Lucile’s customers. Florenz Ziegfeld was so impressed with some of Lucile’s models that he asked if he could employ them in his Follies.

These days children grow up watching semi-pornographic pop videos where revealing outfits are the norm. Sex has lost its mystery to become more mundane than sacred. Sex is seen for what it is – a mix of the physical, fun, sometimes funny, surprising and messy. Of course, sex also has its darker side. In addition to the illegal sex trade and people-trafficking, one of the most serious problems we have yet to address is widespread addiction to online pornography and the objectification of women.

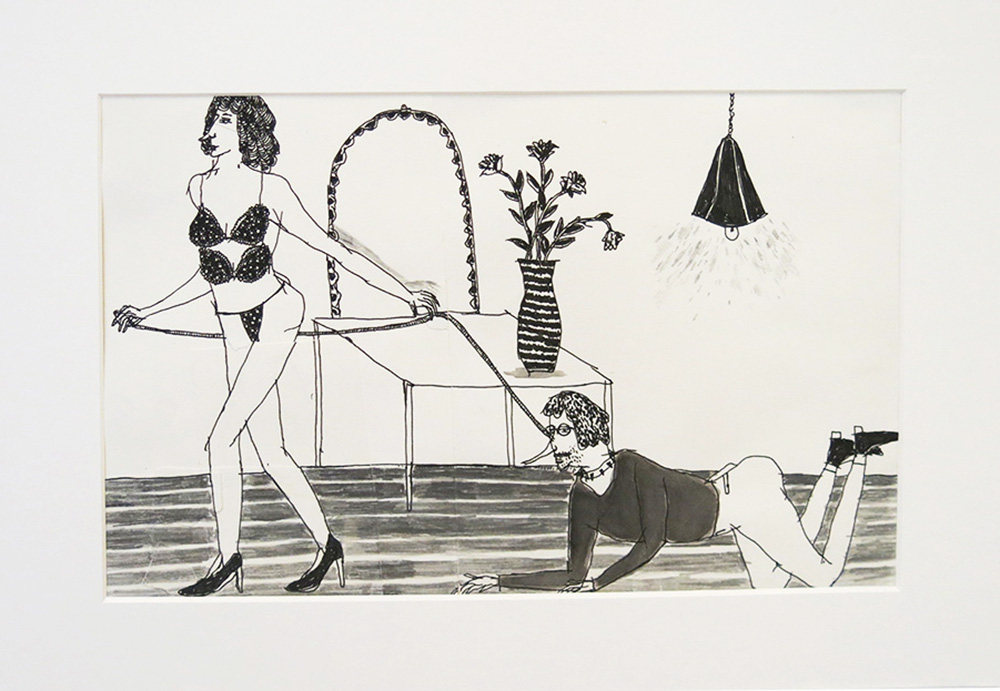

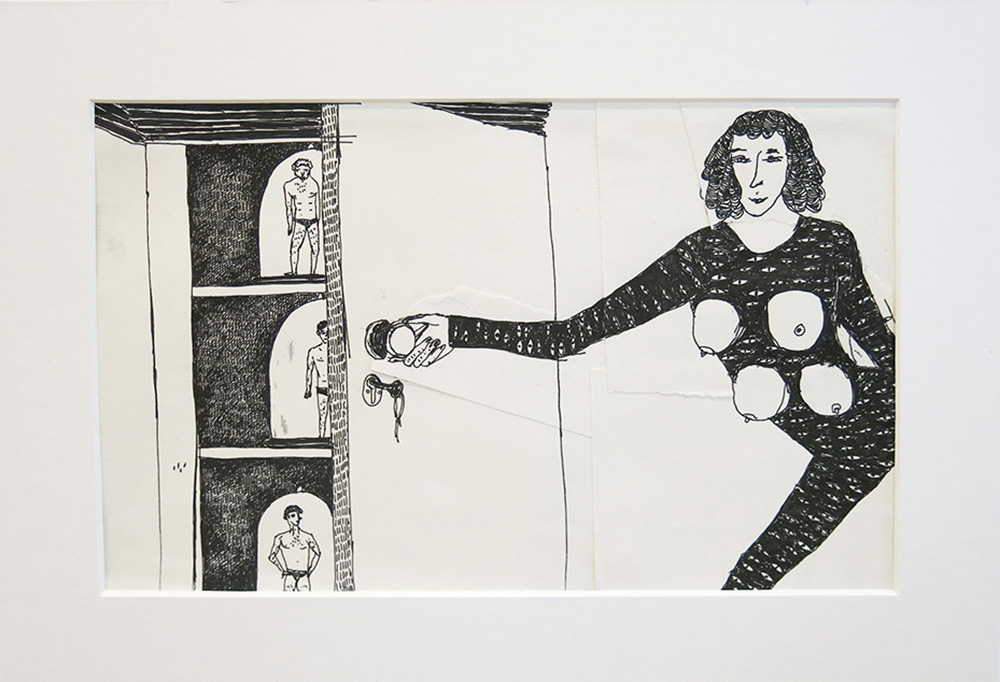

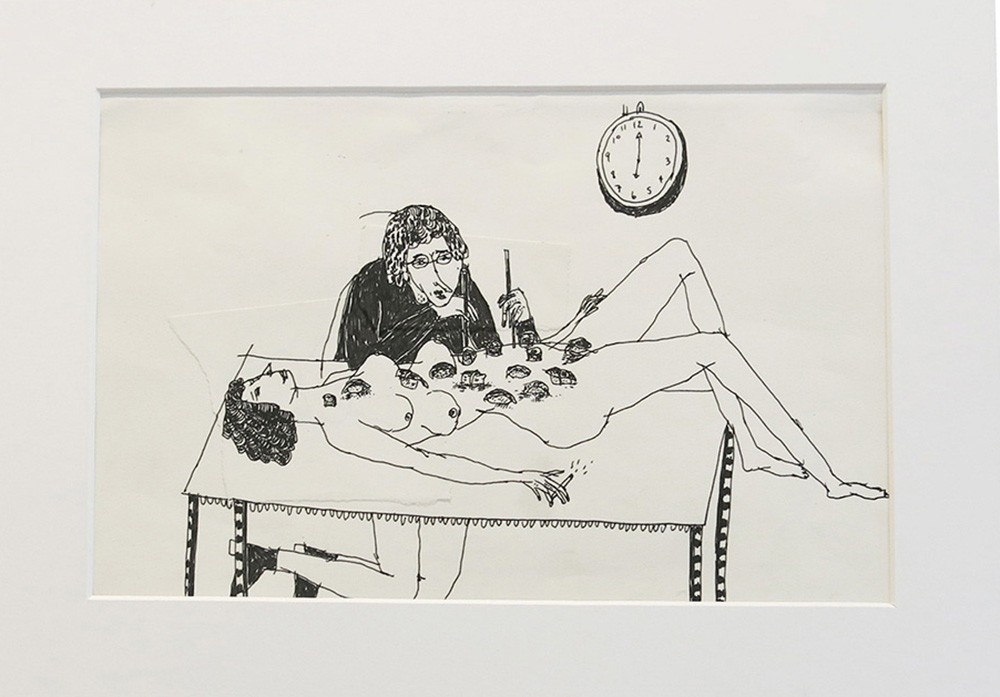

Sofia Drescher’s illustrated ‘urban fable’ Agatha’s Men addresses some of the problems of pornography. It follows the story of Larry in his hopeless pursuit of a relationship with the woman of his fantasies. Several of the original ink on paper illustrations are shown here.

Other artists have also used comic effect to highlight serious issues. Julie Verhoeven’s immersive installation, Whiskers Between My Legs, at London’s ICA emphasized the playful side of sex, but also toyed with our perceptions of gender and taste. Mainly known for her work in illustration, fashion and textile design, Verhoeven used an array of collaged fabrics to create a ‘grotto of visual excess’ exploring ideas of femininity and how they are expressed in popular culture. The installation was accompanied by a film covering themes such as female seduction, titillation and perversion, played through TV monitors placed inside the basins of quilted toilet seats.

Other artists have also used comic effect to highlight serious issues. Julie Verhoeven’s immersive installation, Whiskers Between My Legs, at London’s ICA emphasized the playful side of sex, but also toyed with our perceptions of gender and taste. Mainly known for her work in illustration, fashion and textile design, Verhoeven used an array of collaged fabrics to create a ‘grotto of visual excess’ exploring ideas of femininity and how they are expressed in popular culture. The installation was accompanied by a film covering themes such as female seduction, titillation and perversion, played through TV monitors placed inside the basins of quilted toilet seats.

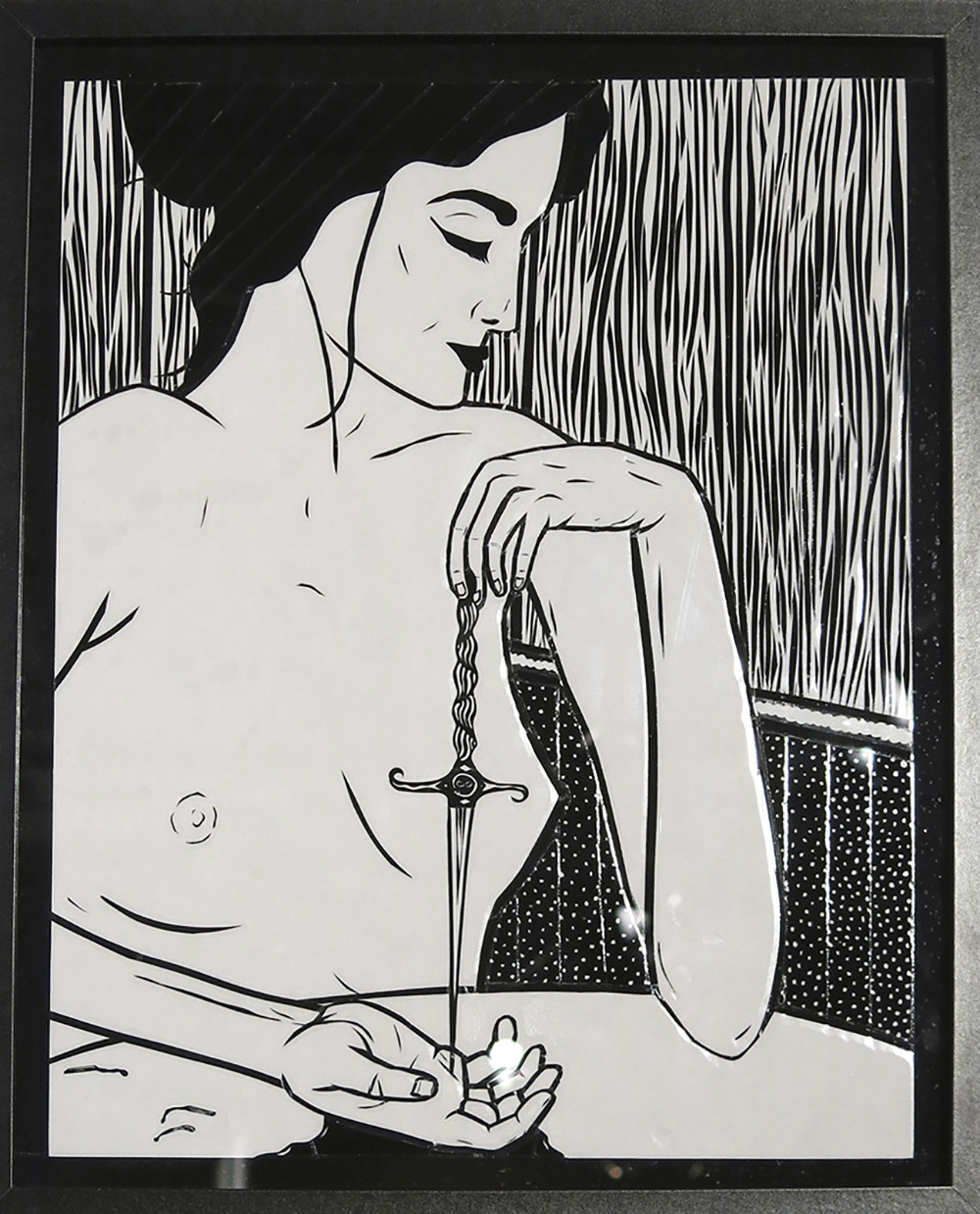

What once seemed decadent is now mainstream – so is the femme fatale still enough to inspire erotic art? Benjamin Murphy needed the added assistance of electrical insulating tape to create his Japanese woodcut style artworks (below, photographed through glass). But, in the post 50-Shades age, even BDSM is considered to be light-hearted fun.

Read more on Sex, Suffragettes and Succès de Scandale in Visuology Magazine Issue 3.