All of This Belongs to You: Them, Us and Our Machines

No, it’s not a load of bollards, though there is one in the V&A’s latest exhibition, All of This Belongs to You. The stainless steel bollard in question (SP 400 by ATG Access), located amongst the railings and public signs of the ironwork gallery, is the type used in many of our public spaces, including the Olympic Park and Stratford’s Westfield Shopping Centre. Much like an iceberg, a large part is concealed underground, enabling it to withstand the impact of an articulated lorry travelling at 40 mph. You probably would never have guessed that these mundane looking ‘civic objects’ cost a cool £10,000 apiece – though perhaps it’s not such a high price to pay for our safety and security?

This free exhibition is partly about the museum as a public space for the appreciation of objects and their provenance, and partly a stage for debate inspired by the objects, their stories and the role of the museum in contemporary life. As well as four installations created by invited architects, designers and artists, there are 40 new acquisitions on display – and loans, including the hard drives that held documents leaked to the Guardian newspaper by Edward Snowden, which were ordered to be destroyed by the UK government.

Specially curated displays are dotted around the museum, which is great if you need to get a bit of exercise. Ways to be Public, a display of architecture projects, is downstairs by the Medieval and Renaissance galleries. You’ll have to make a detour to the Cast Courts to see Jorge Otero-Pailos’s conservation latex ‘cast of a cast’ of Trajan’s Column. Ecologist Natalie Jeremijenko’s ‘Ag Bags’ are to be found outside the museum, bringing new plant life to South Ken. And Ways to be Secret (inevitably the most tricky to locate) is upstairs in the 20th century wing.

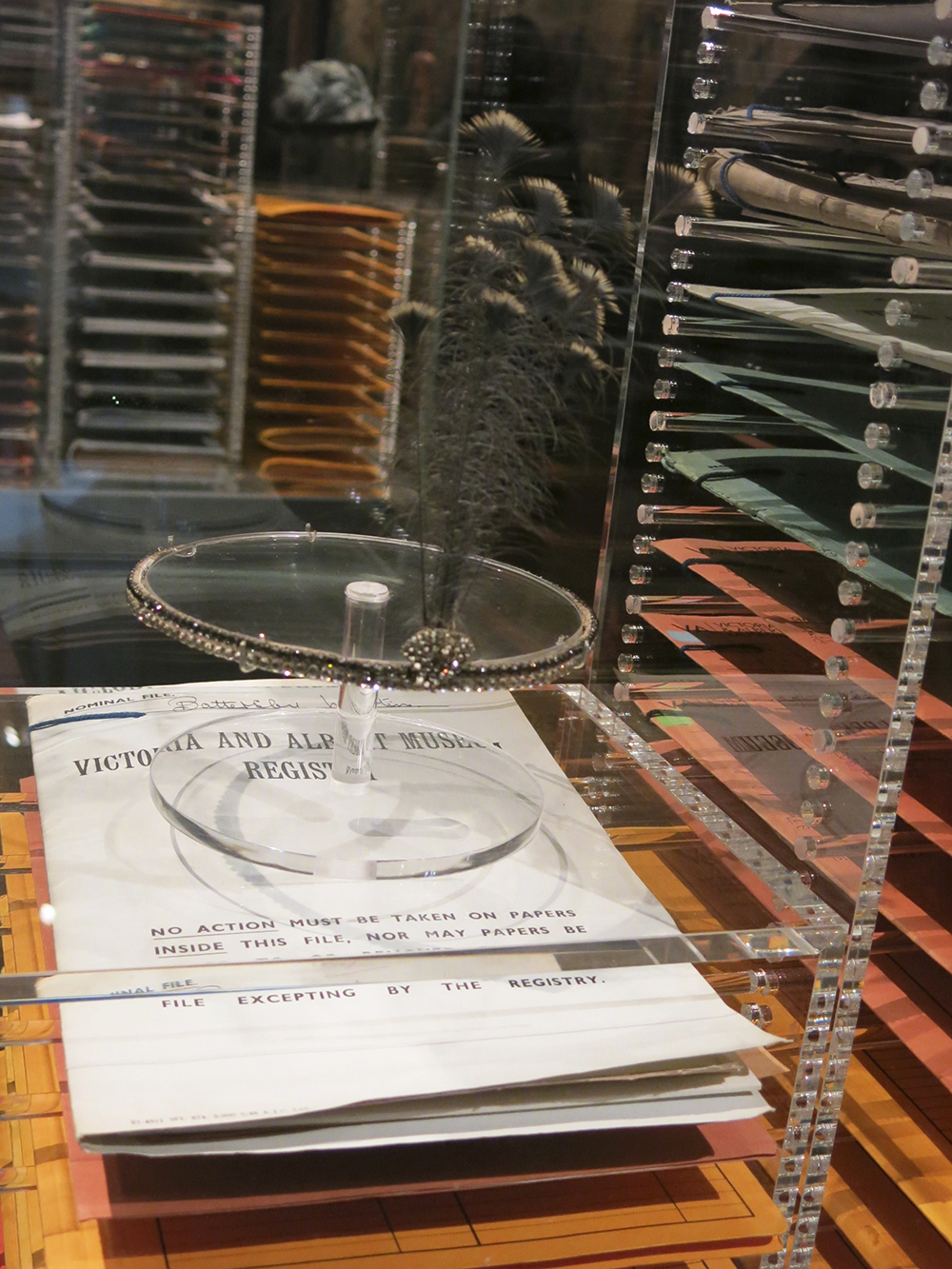

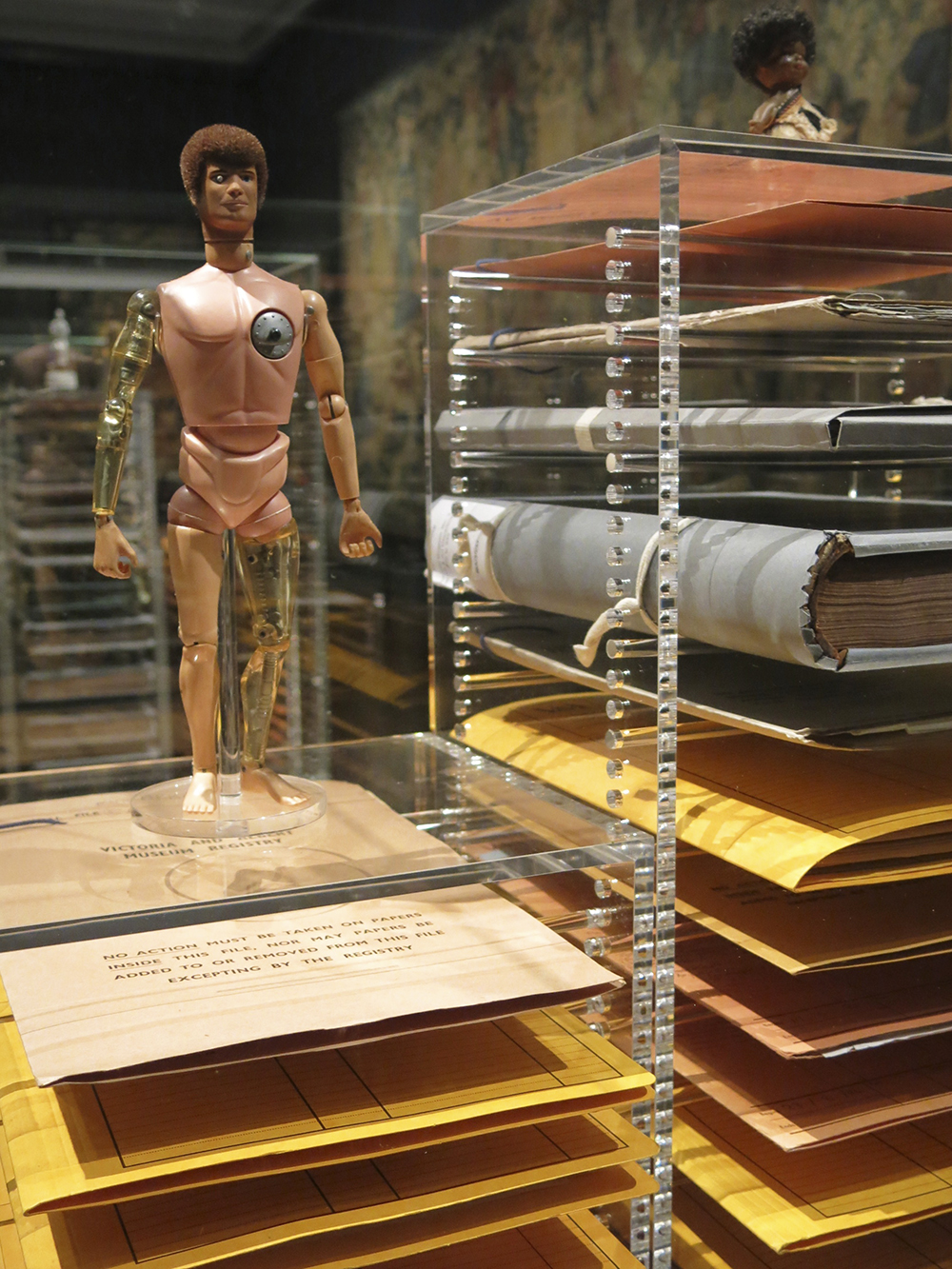

James Bridle’s installation in the tapestry gallery is perhaps the most prescient in its depiction of what belongs to us (and to others). Five Eyes takes its name from the alliance of major English speaking intelligence powers – Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the USA. Objects have been automatically selected from an analysis of the musuem’s 1.4 million digital records, using an algorithm of the sort employed by the agencies. Each of the five server-stack style displays includes archive files and linked objects revealing the provenance and unexpected connections (based on tags) between the items, as well as the history of intelligence and how it shapes the world.

Digital records can also be used to discover things about and links between people. As Bridle points out in his blog, NSA General Counsel Stewart Baker once said, “metadata absolutely tells you everything about somebody’s life. If you have enough metadata, you don’t really need content.” During a debate at John Hopkins University in April 2014, Michael Hayden, a former Director of both the NSA and the CIA, confirmed that position, and went further: “We kill people based on metadata.”

Bridle describes ‘big data’ as “both a promise and menace.” It plays into our universal desire to know more about the world, and to operate in it more efficiently, but downplays the extent to which the world is shaped by the data that we choose to gather, the technology that gathers it, and the politics of those who design that technology. We inhabit a world where decisions are “increasingly made by unknowable machines – a banal recreation of the present, constructed from the traces of phone calls, credit card transactions and voting records.” Bridle says: “We must take responsibility not only for our own actions, but the actions of the vast non-human assemblages we have built around us – from corporations to complex software systems – and acknowledge the moral and physical limits of our technologies, and ourselves.” The museum, the software programme and the intelligence agency have similar ends – they attempt to order and structure things in ‘the right way,’ for our common benefit. As Bridle points out, “The curse of omniscience, once attributed to God, is now more tragically invested in the machine.”

As digitization increases exponentially, the expansion of technology into all areas of our lives continues apace. The ‘block chain’ is seen by some to be a universal panacea to all our needs. With block chain powered product histories, we will all be able to track the history and provenance of every purchase we make. Everything will be up front and traceable. Meantime, fascinating secrets of our material culture and lifestyles may well remain hidden away in museums… perhaps waiting to be unearthed by future generations of machines that, hopefully, will still belong to us.